The Young Woman Who Changed the World’s View of Chimps, and of Ourselves

On 14 July 1960, a 26-year-old English woman stepped off a boat at Gombe Stream Game Reserve, Tanzania, to begin what would become one of the most revolutionary studies in the history of science.

Her name was Jane Goodall, and her quiet determination and radical curiosity would soon transform our understanding of chimpanzees, and of what it means to be human.

Goodall had no formal scientific degree at the time. What she did have was an unshakable love for animals, nurtured since childhood. “Apparently, from the time I was about one and a half or two, I used to study insects”, she later told the BBC. “Then I read Dr. Dolittle and Tarzan, so, of course, it had to be Africa.”

A Chance Meeting That Changed Everything

After finishing school, Goodall worked as a waitress and film production assistant to fund her dream of going to Africa. In 1957, she finally made it to Kenya, where she met the famed palaeoanthropologist Louis Leakey.

Impressed by her passion and knowledge, Leakey hired her as his assistant, and later chose her to lead a study on wild chimpanzees.

Leakey believed her lack of academic training was an asset. “He said my mind wasn’t ‘hemmed in’ by scientific dogma”, Goodall recalled.

Gombe: The Beginning of a Remarkable Journey

To comply with colonial safety regulations, Goodall’s mother, Vanne, accompanied her on the first months of the expedition. Life in the Gombe forest was difficult; both caught malaria, and the chimpanzees fled whenever humans approached.

But Goodall’s patience and empathy paid off. She wore the same clothes every day, moved quietly, and never forced interaction. “Gradually, they came to accept that I was harmless”, she told the BBC’s Witness History.

From a hill overlooking two valleys, she began observing the chimpanzees through binoculars—recording their behavior, interactions, and emotions with unprecedented detail.

Groundbreaking Discoveries: Chimps Use Tools and Show Emotion

One of Goodall’s most stunning findings came when she watched a chimp named David Greybeard strip leaves from a twig to catch termites. Until that moment, toolmaking was believed to be a uniquely human trait.

“Chimpanzees use more different objects as tools than any creature except ourselves”, she explained. “They use sticks for feeding, crumpled leaves for drinking water, even stones and branches as weapons.”

Her observations shattered scientific assumptions and forced experts to rethink what separates humans from animals.

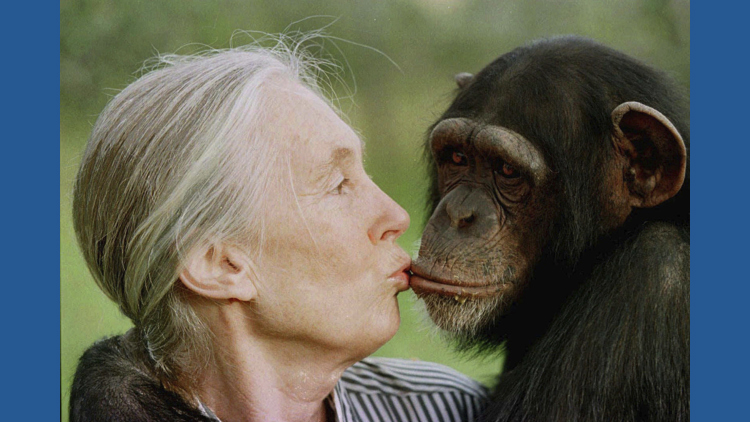

Goodall also noticed their social complexity: they hold hands, hug, kiss, and show affection after reunions, behaviors once thought to be uniquely human.

“They act as gentle, protective fathers and maintain close family bonds”, she said.

Challenging Human Assumptions

By naming her subjects instead of numbering them, Goodall emphasized their individuality. She revealed that chimpanzees could be both compassionate and violent, forming deep emotional ties yet also engaging in territorial aggression and even cannibalism.

This duality, she suggested, reflected our shared evolutionary heritage.

“Behavior we see in man today and in chimps today was probably in our common ancestor”, she said. “We can imagine Stone Age people embracing one another, using little twigs to feed, and forming long friendships.”

From Scientist to Storyteller

Encouraged by Leakey, Goodall earned her Ph.D. from the University of Cambridge in 1966, despite never having completed an undergraduate degree. Around that time, the National Geographic Society sent filmmaker Hugo van Lawick to document her work.

Their collaboration produced the acclaimed 1965 documentary Miss Goodall and the Wild Chimpanzees, narrated by Orson Welles, and led to marriage and the birth of their son, Hugo “Grub” van Lawick.

A Legacy That Redefined Humanity

Goodall’s discoveries proved that humans and chimpanzees share more than 98% of their DNA, and much of their emotional and social life. Her insights bridged the gap between species, showing that our roots in the natural world run deeper than science had dared to admit.

“Understanding chimps raised new questions about how we raise our own children”, she told the BBC’s Terry Wogan. “We may produce intelligent adults, but if they lack close relationships, perhaps we’ve lost something vital.”

Today, Dame Jane Goodall is celebrated not only as a primatologist but as a global advocate for wildlife conservation and compassion. Her work continues to inspire scientists, activists, and dreamers worldwide.